The New York City Ballet Costume Shop

“As I entered, the workers’ eyes would catch mine then refocus on their tasks, working meticulously to turn abstract ideas into tangible expressions of beauty.”

Nestled away on the 7th floor of the Rose Building at 70 Lincoln Center Plaza, the New York City Ballet costume shop felt like a well-kept secret in the bustling heart of Manhattan. Whenever the shop directors sent requests for maintenance projects, I seized the chance to escape my office in the underground “bunker” below David Geffen Hall.

To reach that enchanting world, I stepped past the Metropolitan Opera stage door, where, down in the staff cafe, Eddie and Francesco crafted the best bacon, egg, and cheese sandwiches, perfectly paired with a crispy hash brown nestled on a toasted English muffin. As I made my way toward the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center, daylight often spilled into the corridor, lighting my way. I liked to pause on the President’s Bridge and snatch a small moment for reflection amidst the chaos. From that elevated perch, I took in the campus views, letting the pulse of the city surround me. Then I’d take the elevator to the 7th floor.

When I first stepped into the NYCB costume shop, it felt like I had discovered a hidden realm steeped in hushed focus and quiet dedication, its only sounds the rhythmic hum of Singer sewing machines and the soft rustle of drapery. As I entered, the workers’ eyes would catch mine then refocus on their tasks, working meticulously to turn abstract ideas into tangible expressions of beauty.

Costume Shop Directors Mark and Jason would approach me with playful grins, their arms crossed in front of their chests, reminiscent of mischievous schoolboys summoned to the headmaster's office. Much like other constituents in the building, they often hesitated to voice their specific requests, whether it was for new clothing racks or adjustments to the pulley systems they used to manage their costumes.

During these meetings, whenever I spoke, my English accent raised eyebrows. Many of the women would smirk and mumble in Russian to one another while smiling in my direction.

Stepping into the Costume Shop felt like being granted a backstage pass to the ballet's secret heart. Principal garments were tagged and personalized with notes on dimensions, size, weight capacity, and fitting dates. I was lucky to witness the process—the sketching, cutting, and sewing that transforms fabric into a dancer's second skin. It was a stark reminder that the illusion of effortless art on stage always begins in a room of meticulous, beautiful work.

The Rose Building

“The clanging of a fire bell echoed ominously, followed by frantic shouts, before a door ten feet to my left swung open…”

After securing a distribution deal for my feature film, in 2013, I applied for and landed the full-time position of Facility Manager at the David Rubenstein Atrium. I was ecstatic—this was a life-changing moment. Not only had the freelance world become challenging and often unrewarding, this opportunity marked my first real full-time job in the U.S., complete with health insurance and great perks.

A few months into my role at the Atrium, the Senior Director of Operations invited me to join the main team, expanding my responsibilities. This transition required moving from the Atrium to an underground office at 146 West 65th Street. My new duties involved assisting management with the daily operations of several prominent venues, including David Geffen Hall, Alice Tully Hall, The David Rubenstein Atrium, the Rose Building, Lincoln Center Theater, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center, Lincoln Ristorante, WNET Studios, 140 W. 65th Street, and three engineering plants.

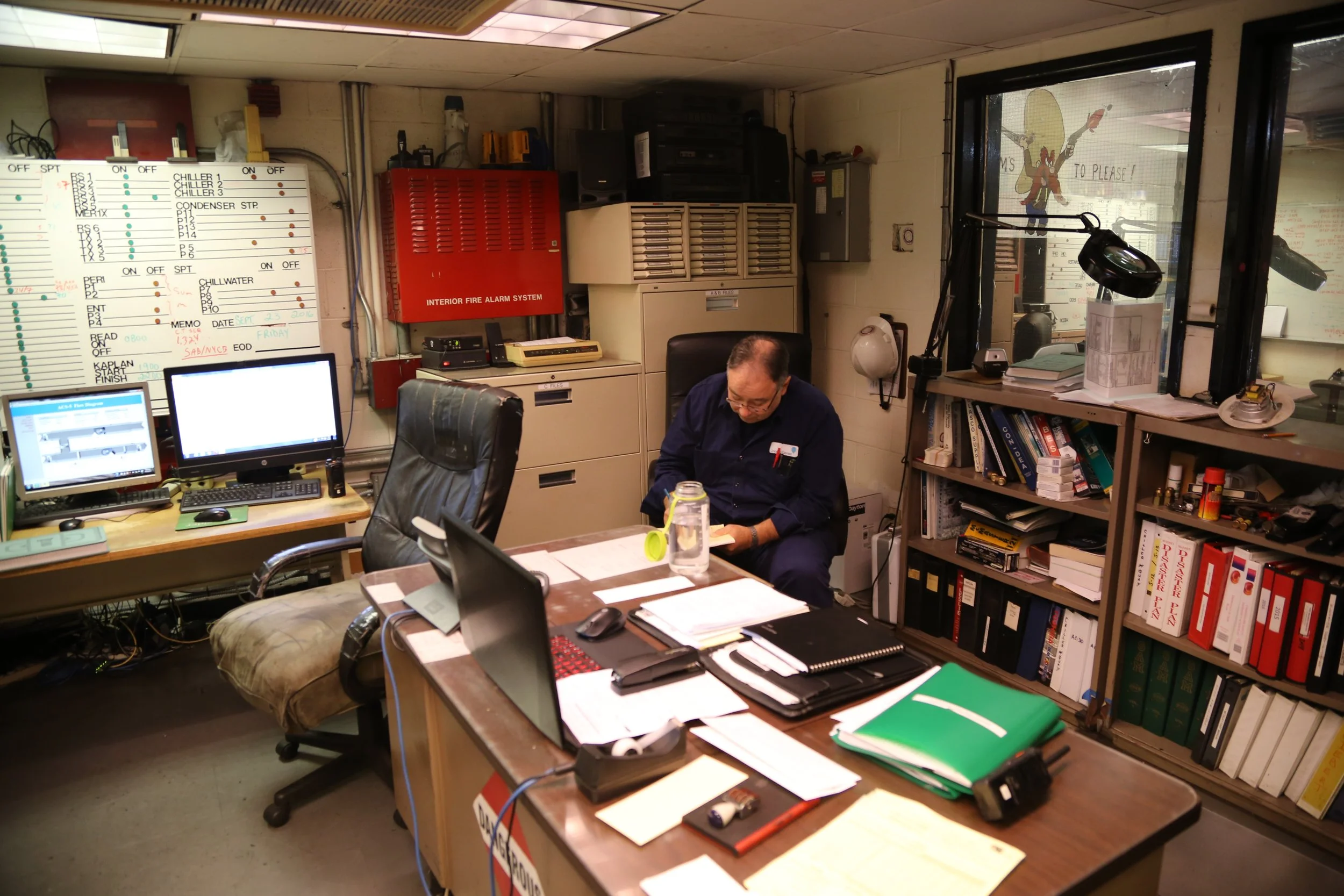

Pete Hoey, Chief Engineer

Pete at Work

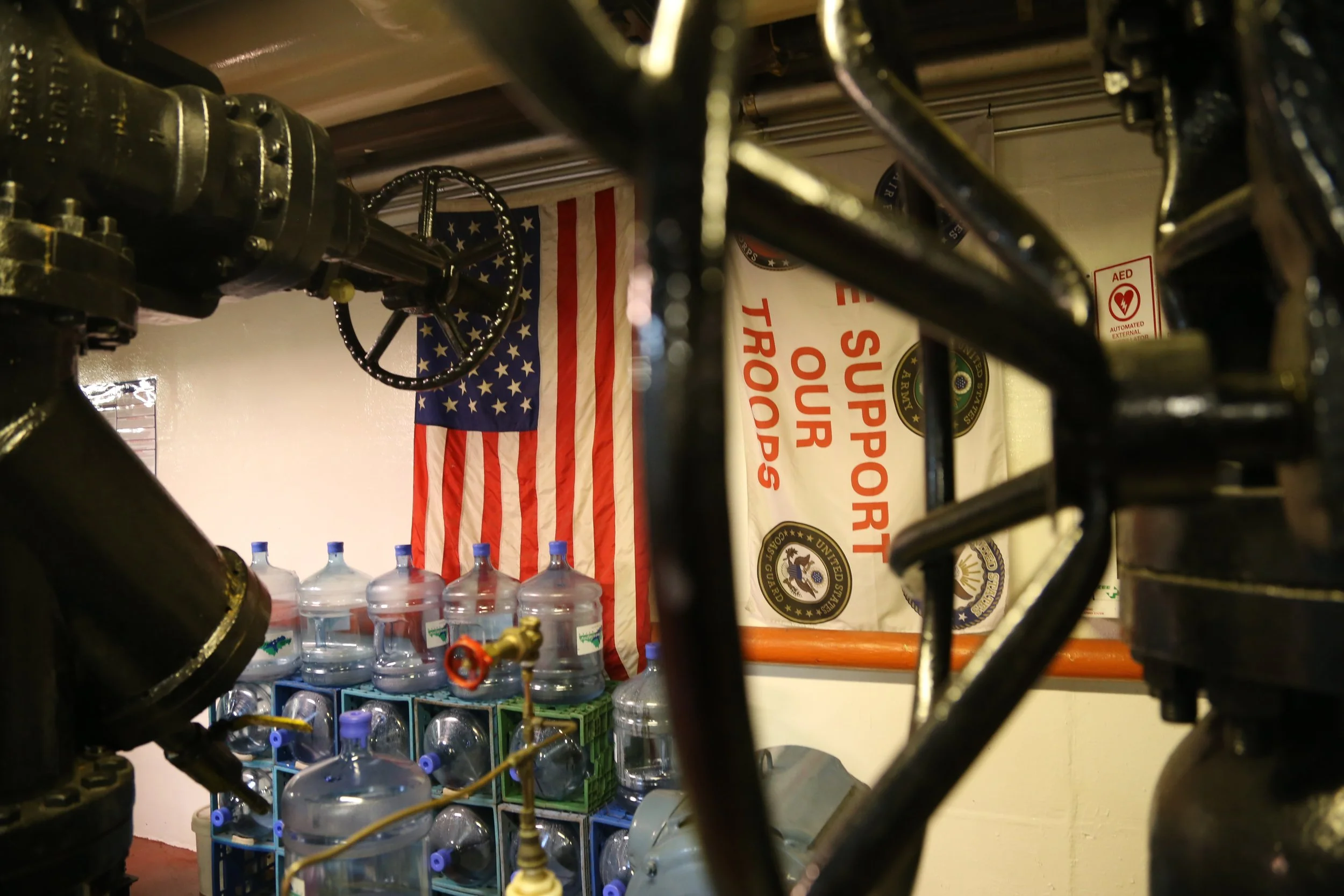

While being introduced to the trade crews, I was sent to meet the Chief Engineer of the Rose building, Pete Hoey. Pete’s domain, the Rose engineering plant, was located three floors below street level and accessed via a dimly lit, soot-ridden tunnel that spiraled down an eerie parking garage. With a nervous frown, I approached the entrance and pressed the doorbell. The clanging of a fire bell echoed ominously, followed by frantic shouts, before a door ten feet to my left swung open and Pete appeared.

On what he affectionately dubbed our five bob tour, Pete guided me through the labyrinth of the engineering plant, a place alive with the cacophonous sounds of machinery. Together, we navigated enormous fan rooms, climbed tiny ship ladders, and treaded carefully across catwalks sixty feet above the iconic stages of Lincoln Center—each step a mix of thrill and trepidation.

Pete’s intelligent and curious demeanor radiated kindness. He took a genuine interest in my background, quickly discovering our shared love for football. He proudly declared himself a lifelong Liverpool fan and, with a laugh tinged by empathy, he acknowledged my allegiance to Arsenal. The rivalry sparked an instant camaraderie between us.

With an endearing softness around his midsection, Pete's wide-faced Irish grin reminded me of a softer James Gandolfini. Yet behind that friendly smile lay a depth of resilience and wisdom from years of experience, making him a reliable ally and mentor in the fast-paced world of Lincoln Center.

Pete became one of the closest friends I made, his sincere demeanor and big belly laughter bringing warmth to an often challenging environment.

Glen and Pete

Glen, Chief Engineer

Glen, Pete’s second-in-command, took the reins as the Chief Engineer upon Pete’s retirement, stepping into the role with equal parts enthusiasm and charm. Our relationship was spirited and boisterous, marked by playful banter.

With a wink, Glen often mocked my management skills, pointing out every little fault with a flourish that was as entertaining as it was educational. In return, I couldn’t resist teasing him for his undeniable good looks and nicknamed him Handsome Glen, joking that he should be the poster boy for Lincoln Center.

Artoo Lincoln

‘Handsome Glen’

I grew to look forward to our spirited conversations which were full of banter. Each time I called the Rose engineer plant, Glen would answer, his trademark fervor booming through the receiver, drowning out the machinery noise around him:

“Rahdgaahh! What the hell do you want!?

Without missing a beat, I’d reply:

“To speak to da most handsomest engineer at Lincoln Center!”

This routine, filled with laughter and camaraderie, cemented our unique bond.

Little Ronnie

Ronnie

I met ‘Little’ Ronnie during a routine plant inspection in the Rose Building. When I mentioned that my wife was away at the National Veterans Memorial and Museum, Ronnie paused, gazing into the distance.

“I’m a Vietnam vet,” he said. “One thing I’ll never forget was that awful smell—like charred meat.”

Glen and Ronnie

Glen Strangling Ronnie

Ronnie described the jungle, where his feet were perpetually damp, and shared grim, admiring tales of his Australian counterparts:

“They were hardcore!” he exclaimed, eyes lighting up. “They made necklaces with the ears of their victims and wore them with pride.”

Ronnie called them Orsies instead of Aussies, in a softer pronunciation, the way a child would say horsies.