Cricket Comes Home

West Indies Cricket Team, 1975

In the summer of 1975 cricket pulsed through my veins. As an intrepid 9-year-old, I was constantly frustrated by Mum and Dad who resisted every one of my attempts to play cricket out by enforcing a strict regime of chores. I hoovered the kitchen and flipped the cushion covers Mum sewed for J.W. Parker—the bronze-faced, silver-haired textile mogul whose factory sat across the street—I swept the stairs, cut the hedge, emptied the bins, and cleaned up after our cat, Kitty.

All labor was enforced by Dad’s belt or Mum’s chubby hand and, if I objected, after a clip on the ear, Mum would say:

“Hear! Me a done cook brekfuss, lunch and dinner back home when me was only seven. Rass!”

But that was in Guyana where children were seen and not heard, where giving licks to your kids was staged theatrically to impress watching neighbors. This was England, where kids had lead toy soldiers and pocket money to buy a 99 Flake from ice cream vans that played Brahms’ Lullaby on a hypnotic loop.

Afternoon jaunts to Brownswood Library with my brother Ron were my only escapes. Even then, sitting between the stacks, lost in Enid Blyton’s Famous Five or Secret Seven mysteries, envy pierced my joy. Child sleuths had adventures in forgotten lighthouses, old barns, abandoned mines, and desolate railway stations, all punctuated by lavish picnics of baked ham, peppermint rock, chocolate biscuits, and ginger beer.

I longed to have adventures like Julian, Dick, Anne, George and Timmy. But we ate pepper sauce instead of peppermint rock, didn’t own an island, and nobody in our family knew how to sail. I became convinced that boarding school was the key to my freedom.

“You wan for go weh?” Dad asked at dinner, frowning.

“Boarding school—like the Famous Five! Then Mum wouldn’t even have to cook for me. Or clean. Or anything.”

“And who go pay for you board in boarding school? Eh? You tink it’s free! Boy hush you mout before me tek a board to you rass and go get me cricket bag ready for de morning.”

My siblings giggled while I backed out of the room. As I pulled Dad’s bat and gloves from the hallway closet, he yelled:

“And remember for put de water bottle in de freezer! Crazy rass boy!”

The following Sunday morning, we were left in Dad’s prized gold Vauxhall Viva outside the Manor House pub for what felt like an eternity.

“What’s taking him so long?” I groaned.

“D’you think he forgot about us?” asked Ron.

“You crazy, he go come soon. Just watch. He better or I’ll kill he rass,” Mum replied.

The car shook from sniggers. Soon Dad returned like a conquering hero, handing out bottles of Coke and packets of cheese and onion crisps to his subjects. We cheered and examined our bounty, savouring the moment before we devoured our treasures like starving Dickensian urchins.

An hour later, the sound of leather upon willow signalled the start of the gentlemen’s game at Parliament Hill Fields, on the Highgate side of Hampstead Heath. Guyanese wives unpacked lunches of roti, curry, fried chicken, aubergine and potato, comparing efforts:

“Eh eh, Mavis, you bygani look nice man!”

“Thanks diddy. I can smell you mango achar from here. You make pholauri?”

“That man love Pholauri! Me rass been a cook since five dis morning!”

I struggled to carry the giant plastic bottle that Dad insisted I half-fill and freeze to ensure cold water all day. We walked past the tennis courts, where women in dainty white skirts wore pearls and hit balls so well that men named Josh exclaimed Good hit! I tried to match Dad’s stride to keep up.

Pottagi, the wicketkeeper—so-called because of his Portuguese background—smiled and said:

“Liccle man a try for walk like he daddy.”

His golden skin, Fu-Manchu moustache, and bright green eyes made me warm to him instantly. I helped him tally runs in the scorebook while he explained acronyms like LBW (leg before wicket), terms like bye (runs scored without touching the ball), and needed run rates.

In between the late morning tea and lunch, I drank frosty orange squash until Ron called me to join the other kids on a nearby wicket. He laughed as oversize pads dwarfed my knees and huge gloves flew off my tiny hands. A huge cheer rang out from the main pavilion.

“Wow, a straight six!” I yelled as Uncle Boodhoo launched a towering drive over the bowler’s head into the trees.

He smiled, smoothed the edge of his regal moustache, spun his bat in the air and caught it with ease.

As the youngest, I batted first. Before I took my place, I imagined how I’d spin my bat if I hit a six. Ron shined the ball on his thigh, staining his jeans dark red.

“OK, this is Andy Roberts’ special fast ball, so watch out!” he cried, starting his run-up.

I held the Gray Nicolls bat firmly despite the loose gloves, tracking the ball’s bounce just as Dad had taught me. It pitched two feet in front of me, rose, and I clipped it over my left shoulder using its momentum.

“Nice shot,” Ron gasped.

I smiled as the ball trickled down the grassy slope. Little Frankie chased it—and then a loud whack! resounded from the main pitch. More screams and yells. Uncle Boodhoo again! But this time, all eyes turned in my direction. The harsh sun blinded me. A dark shadow loomed overhead.

Just before the rogue ball smashed into my skull, Pottagi’s hand plucked it from the air.

“Oh rass, I thought the ball go buss he head!” Dad shouted, running over, as Uncle Boodhoo breathed a sigh of relief.

Dad grabbed my arm and handed me off to Ron.

“Go stand inside. It’s too dangerous out here for you, boy!”

“You okay?” Ron asked, hauling me like a five-year-old. I wriggled free, but Dad yelled:

“Go sit inside de pavilion, now!”

Humiliated, I sulked while the others enjoyed the rest of the idyllic afternoon. Pottagi caught my eye, shrugged, and winked, forcing me to smile.

On the first day of the inaugural Cricket World Cup, Dad stood proudly in front of the telly in his whites, blocking the view of numerous rum-drinking partisans as he reeled off the names of his favorite players:

“Clive Lloyd, Rohan Kanhai, Alvin Kallicharran, Roy Fredericks, Lance Gibbs! You know where dey come from, bai?”

“No,” I replied, feeling caught out.

“Come,” he said, striding from the TV to the back of the living room.

“Yes man, move you rass!” yelled Uncle Narine as the screen reappeared.

Dad smiled, proud, and pointed to the wall where a black cloth map hung, embroidered in red and gold thread: Guyana, South America.

“Guyana! Dey all from Guyana, where we is from! Is five players from Guyana in de West Indies team, bai! More than any other rass country. Dey gon buss dem English rass!”

I giggled and looked to Ron for confirmation. He nodded, lifting his NHS specs for a better view—only for the scotch-taped lens to pop out for the umpteenth time.

“Oops!” he said, as everyone turned from the TV.

In a flash, Ron’s hand swooped and caught the lens. He rejoiced like he’d captured a vital English wicket.

“Good catch to rass, boy!” Dad hollered as Ron reattached the lens with a smirk.

There was spontaneous applause from the crowd on the sofas: Uncle Sewha and his boys, Michael and the Meshes—Ramesh and Omesh. Uncle Harris, the small, quick-witted electrician from Paddington, his wife Aunty Betty who had the highest pitched voice, dirtiest laugh and a wicked sense of humor, their two sons Frankie and Georgie, who wore smart blazers for the occasion, Uncle Narine, Dad’s hot-tempered best friend, his wife Auntie Jay and their three kids who always stood in ascending order of height.

We watched nothing but cricket for hours and, when the umpire called lunch, we played cricket in our tiny concrete garden. Dad bossed the games, wielding a yellow plastic bat, while Ron and my three sisters fought to bowl him out. Nadira’s bulky frame made her, as the oldest, also the fattest. Jenny and Lita fielded next to her, their skinny frames swatted aside, as she charged after the ball. I positioned myself behind Dad, fancying myself as a wicketkeeper like my pal, Pottagi.

“Howzzaaaat!” I leapt in the air and yelled as I caught him off an outside edge.

Dad roared with laughter, coughing and spluttering before saying:

“You been a watch dis game close na bai?”

Two weeks later, the West Indies played Australia in the World Cup final at Lords. By then I knew the names of every player, even Dickie Bird, the infamous English umpire, whose flat white cap and shoes to match became his trademark attire. Mum flung our bay windows wide open to release the billowing cigarette smoke coming from the sofas. Just as Clive Lloyd hit the first six of his magnificent innings, a dramatic breeze lifted Mum’s home-sewn net curtains to salute the West Indies’ captain.

“Six to rass!” yelled Dad, jumping from his chair as if he himself had connected with the ball to send it into the crowds.

On the TV, bare-chested West Indies fans blew whistles, banged cans and danced in celebration, mirroring the euphoria in our front room. Uncle Rudy, our upstairs tenant, muttered to me in his educated Guyanese accent:

“You know what a six is? Is when de ball pass de boundary widout bouncing.”

He shared this pearl of wisdom, swigged his whisky, and never once took his eyes off the game.

Ron and I barely tasted dinner. We dashed to the front room any time there was a raucous cheer. Mum and my sisters cooked tirelessly for the hordes of colorful visitors. As Mum dished up plates of chicken curry and rice, a loud commotion came from the hallway as Bora-Poke arrived wearing his signature pork-pie hat.

James Bora-Poke, exhilaration epitomized, never failed to roar his presence when he entered a room. He talked, adrenalized, drank volumes more than anyone else and cussed like a Caribbean pirate the more he drank. He bounced into the kitchen, breathless, hugged Mum and grabbed the plate of food on offer before Uncle Harris’ outstretched hand could claim it.

“Boy you rass got no shame!” Uncle Harris smiled, irked but used to his friend’s overexuberance.

“Harris brudda, mi bougie here mek me favorite ting man and me a run from work for see dis rass game. Come man, teka drink, you see there nuff food for every rass skunt here!”

Uncle Harris shook his head as Bora Poke stomped to the front room, devouring his curry while we kids beamed at his awesome character.

The Australians were getting run out left right and center, by Viv Richards with his deadeye for the wicket. As the sun faded, twilight shimmered and graced Lords. West Indian fans danced jubilantly inside the boundary as the final Aussie wickets tumbled. Dennis Lillie and Jeff Thomson’s last stand kept the Windies crowd heaving in anticipation of glory.

I watched as Bora Poke snuck over to the record player and slipped on the Wet Dream LP. He shushed me with a finger to his lips, then flashed that wicked Bora Poke smile full of sparkling gold teeth.

While Max Romeo sang the lusty lyrics of The Horn, a calypso favorite—If we bend bend bend, you see de rear end, dem a walk and a g’wan, dem give you de horn—Derrick Murray stumped Jeff Thompson and sprinted to the pavilion hugging the stumps after claiming the last Aussie wicket and soon Clive Lloyd lifted the first ever cricket World Cup for the West Indies.

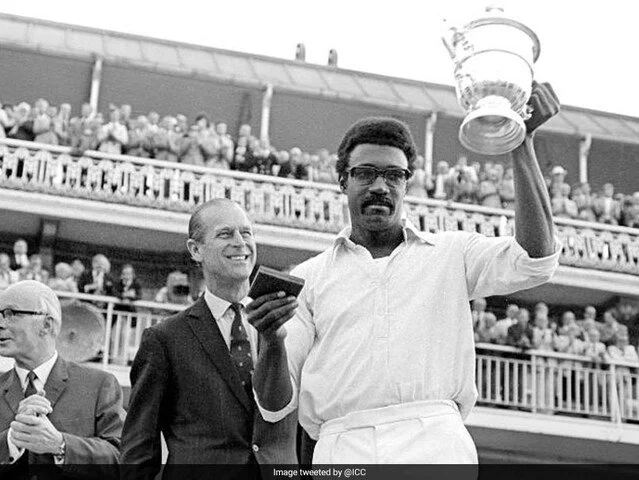

Clive Lloyd, Guyanese captain of the West Indies

Uncle Narine bit the stopper out of a bottle of El Dorado like a swashbuckling pirate and spat it across the room where Bora-Poke caught it.

“Out for a duck rass!” He roared and they howled with laughter.

Bora Poke poured a drop on the floor, “It’s for de dead,” he whispered, winking at me and turning to fill the waiting glasses. Dad eased Bora-Poke from the stereo and turned the music down. He took a swig of whisky and exhaled as the room turned to him:

“A toast...to de West Indies and Guyana, world champions to rass!”

A huge roar went up. Ron and I grinned at each other and leapt in the air, spilling our cups filled with real Coke, not Sainsbury’s Cola, for the special occasion. Dad slipped on a 45 with a His Master’s Voice label and pumped up the volume. Mum tossed her apron, swallowed the remnants of a chicken roti and rested her hand on his shoulder. The carpet heaved from the jump ups and jerks of fifty cricket-crazy, drunk and deliriously happy Guyanese.

Dad smiled at the world as the stylus jumped across the vinyl of his favorite local Indian song by Kishore Kumar—Gori oh gori, chori oh chori—Everyone was smiling, singing, dancing, sending prayers or whispers of thanks. I looked at Ron and he smiled, sharing the goosebump moment. My sisters bopped shyly alongside Mum and Dad.

I stood in the middle of it all, watching one of the most bizarre and wonderful spectacles I’d ever seen—Cricket had come home.